Using foresight to build food systems capacity

By Shem Omasire, Daniel Odediran, and Fisayo Oyewale (hub focal point)

In November, we attended a week-long capacity-building workshop hosted in Naivasha, Kenya, on foresight and food systems. We represented the Next Generations Foresight Practitioners’ (NGFP) Rural Futures hub, one of the four sectoral hubs within the NGFP network. Capacity building is one of the hub’s three main approaches, in addition to advocacy and convening. The workshop, hosted by Foresight4Food and supported by Mastercard Foundation, Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA), African Food Fellowship, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), focused on leveraging foresight for food systems change, using Naivasha’s horticultural sectors as a case study, drawing over 50 participants.

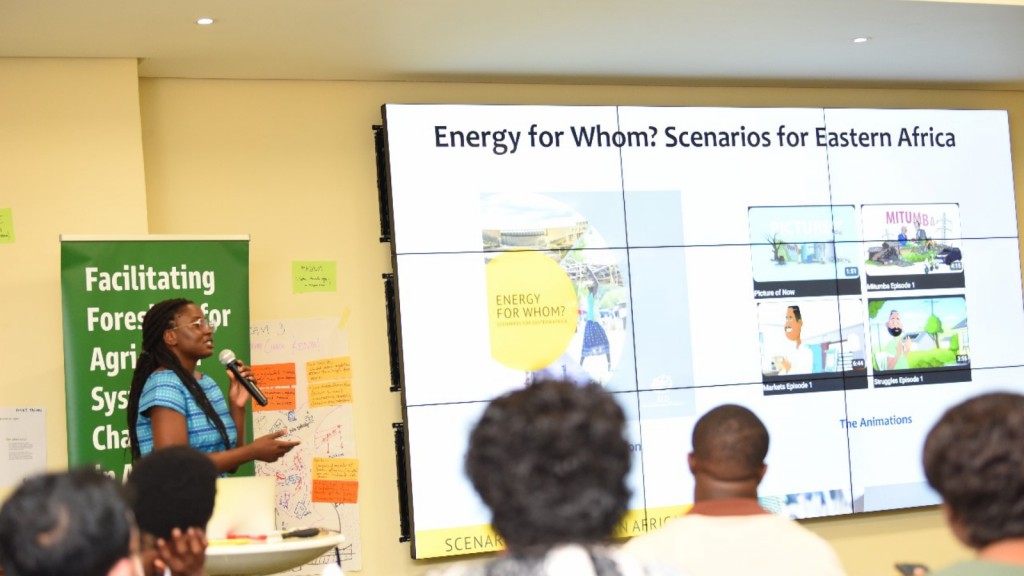

Passy Amayo Ogolla, NGFP’s Advocacy Lead and Africa Network Weaver, delivered a compelling presentation on scenario use in futures projects and the impactful role of animations in broadening the accessibility of foresight outputs, emphasizing its democratizing aspect in engaging diverse audiences. This aspect corroborates with a comment made by SOIF Founder, Cat Tully, at the recently concluded Dubai Futures Forum, where she mentioned that foresight is about “empowering people to use ideas about the future to create change.”

SOIF and NGFP emphasize the influence of networks, exemplified when a Rural Futures Hub member, Shem, received an invitation to join another food systems workshop in Machakos, Kenya the subsequent week. This event, the Utafiti Sera Workshop, organized by the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR) with support from IDRC, delved into pivotal policy matters addressing worldwide challenges like hunger, poverty, and the climate crisis.

The event in Naivasha began with establishing what foresight is, why it’s important for agri-food systems, and an overview of the horticulture sector. Below are our four takeaways from the workshop.

- A Well-Paced and Inclusive Process

Most NGFP Rural Hub members are well-versed in the theoretical aspects of foresight, as alumni of the SOIF foresight training program. Additionally, the various foresight projects that the NGFP members have engaged in, both at a personal level and collaboratively, have given us the practical experience in not only the art of facilitation, but also the use of various foresight tools used across the four-stage foresight process (Scoping, Ordering, Investigating, Integrating). Accordingly, one of the major takeaways from the workshop was process-wise, largely concerned with the art of facilitation.

When facilitating a foresight exercise, it is imperative not to let the participants get too bogged down by ideating, a stage that one can possibly spend several hours on. Cognizant of time constraints, the facilitator should encourage the participants of any foresight process to quickly come up with ideas and swiftly move on to shaping and moulding these ideas within whatever context they are working on. There’s an unlimited number of ideas that one can formulate; hence participants should take the few that they have come up with and essentially “get the train going”.

Another essential aspect of group facilitation is ensuring equal participation and representation of everyone’s perspectives. Participants vary in temperament, with some being outspoken and dominating discussions, while other, despite possessing valuable insights, might be quieter and more reserved. This situation is a golden opportunity to practise the “art” of foresight, because it entails a balance of getting everyone to speak up while not letting the need for consensus slow down the process. All in all, as facilitators of group foresight, time is one of the major constraints and it is a key role to ensure that the process flows smoothly within the allocated time.

One interesting bit was that stakeholder mapping was done prior to the engagement where all participants found that they had been allocated different stakeholder groups, that is, large scale producers, SMEs, government, logistics, consumers, and others. This allocation was done so as to ensure that each perceived stakeholder within food systems had a voice within the room, regardless of whether or not the particular individual resonated with the particular stakeholder they had been assigned. This process was helpful in identifying various roles of players and where collaborations are needed to effect change.

The groups additionally went on four field trips to engage with various stakeholders – farmers, wholesalers, retailers, and exporters. The insights from the field trip expanded the perspectives needed to assess key trends and critical uncertainties within food systems. Participant-facilitators led various activities throughout the workshop, including mapping the pathways for food systems change timeline by 2050.

- The Art of Communication

The art of communication and its importance was also heavily felt within the workshop. Inundated with so many new concepts and information, oftentimes the participants get overwhelmed, and find it hard to follow through with the train of thought. This is where the importance of soft skills such as communication shone through. Arguably one of the best facilitators we had was not necessarily skilled in issues foresight, but was quite adept at explaining through the dense theory to resonate with a majority of the participants. Therefore, as facilitators who might find ourselves working with people that may not be scholarly, literate, or even old enough to be considered informed (think children under the age of 10), it’s important to learn how to communicate concepts in an easy to grasp manner.

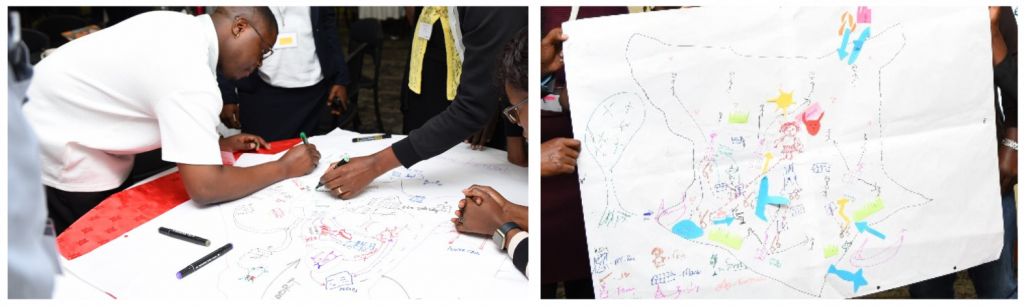

- The Rich Picture Tool

One of the most engaging tools that we used during the workshop was Rich Picture. The fact that you were required to come up with one single image within the groups that you were working with that would represent whatever idea it was that you collectively had was both challenging and exciting.

Picture this: Seven to eight participants around one table, each with a marker pen, ink pen, and /or sticky notes in hand. The facilitator comes round and encourages you to start drawing, whether or not you even know what you want to draw. Yet, you start. Remember the time constraint. So half of you on the table are drawing one thing or the other on the large sheet of paper, while others are ideating, others making paper cut-outs to represent various things, and others are writing on the sticky notes to compliment the drawings. It’s a chaotic process to say the least. However, beauty emerges from chaos and several minutes later, you have a complicated picture that communicates several of the ideas that you have as a group. The crucial role of delegation comes in when working with rich pictures, since everyone will have a role to do whilst contributing positively to the evolution of the picture.

- The Importance of a good theory and foresight

As people who spend quite an amount of time developing, and interacting with theoretical content, sometimes you wonder about the lack of translation of such theory to practical work. This has the tendency sometimes to bring frustration since you might wonder why this excellent piece of work that you created has not yet been implemented to the benefit of the people, as they say in Kenya, “on the ground.” Two foresight gurus, however, suggested two bits of information that showed the necessity of theory, as well as the practicality of foresight work beyond immediate grassroot impact. The first was Jim Woodhill, chief facilitator during the workshop, and member of Foresight4Food, who mentioned a quote by the late social psychologist Kurt Lewin:

“There’s nothing as practical as a good theory.”

Pretty much self-explanatory, no?

The other critical insight came from Professor Julius Gatune, who mentioned that the purpose of foresight is essentially to broaden the scope and horizons of strategists. In this regard, the impact of foresight is nuanced such that, yes, you may fail to see the connection between the particular foresight project or outputs and implementation. However, Prof. Gatune mentioned that foresight is vital as it widens the scope of those involved in strategy, whether as individuals or as entire departments. There are so many possibilities that would have remained hidden to such strategists, but due to the “broadening” nature of foresight, the possibilities in consideration are enhanced. This insight is related to one provided by Peter Shwartz in his 1991 book The Art of The Long View, where he said:

“It is this ability to act with a knowledgeable sense of risk and reward that separates both the business executive and the wise individual from a bureaucrat or a gambler.”

The Rural Futures hub comprises members with experience and expertise in food and agriculture, rural development, policy, youth engagement, and business support coming from Africa, Asia, and other continents. With activities cutting across engaging grassroots stakeholders, farmers’ futures, futures of food systems, rural-urban migration and many more, the hub utilises foresight tools and methodologies to reimagine the futures of rural communities, starting with Africa. As members of the Rural Futures hub, we plan to harness the insights from the workshop and localise some of the methodologies and tools among the communities we will be engaging for our projects in 2024.